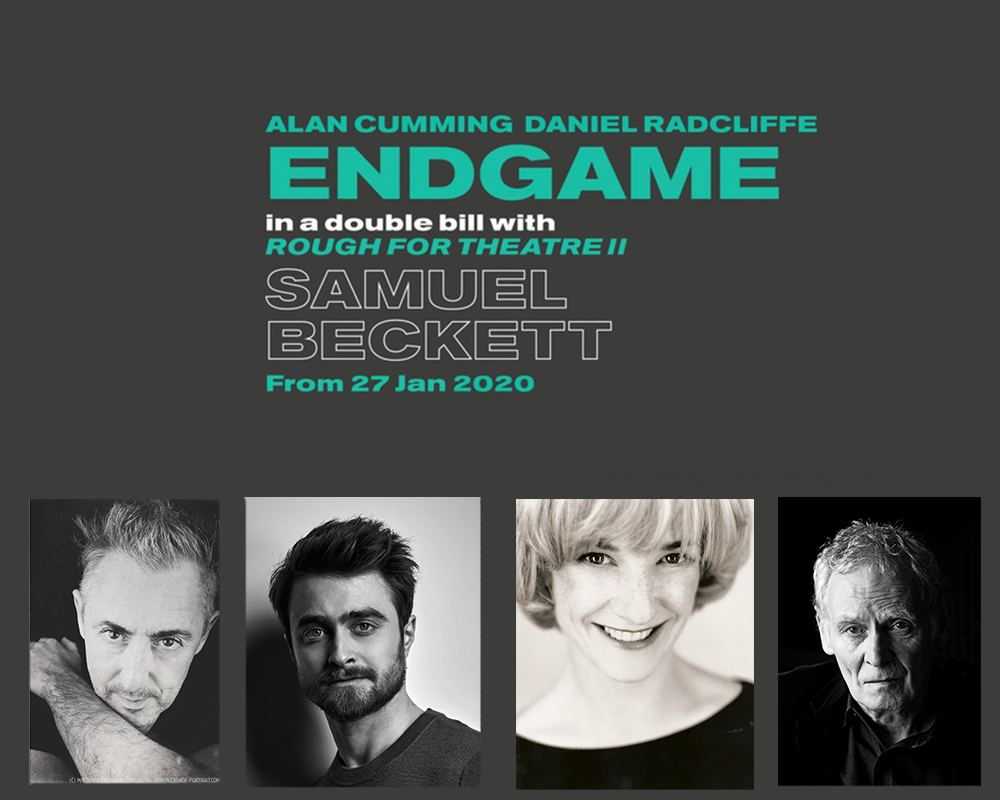

Weekend Women: Endgame review by Tina Cook QC

Endgame – Samuel Beckett (1957) at

The Old Vic

‘Can there be misery lovelier than mine?’ asks Hamm rhetorically at the opening of Samuel Becket’s 1957 play, ‘Endgame’. I was not entirely prepared for this. A Monday evening should justifiably be a comfortable start to the week, a gentle balm to the senses already exposed to one day of lever arch files, post-it notes and confrontational arguments. So, resetting my Monday evening mindset to deal with the mercurial genius of Alan Cumming’s character Hamm took a conscious effort.

But, the circular flow to Beckett’s ‘Endgame’ was surprisingly captivating. Hamm is virtually immobile in his chair centre stage whilst his servant, Clov – played by Daniel Radcliffe – revolves around him in pointless repetitions of meaningless chores whose function is simply to fill the vacuum of their existence. The trick that kept me – and presumably the rest of the audience – fascinated by this bizarre interaction was the thought that somehow they might, just might, be redeemed.

Which is where the two galvanised wheelie bins, sunk into the stage floor front right, come in. Inside are Hamm’s parents. Of course! Who else would hold the keys to the meaning of such a ridiculous existence other than one’s parents? Flip back one lid, and up pops Karl Johnson as Nagg (Hamm’s father); flip back the other, and there’s Jane Horrocks as Nell (Hamm’s mother). I quickly reassessed the prospects for redemption. Er, nil. I’d forgotten that inhabitants of the Theatre of the Absurd are there for a reason and in this case, their reason was to confirm that the DNA they shared with their son was not going to save him.

‘Is it time for my painkiller?’ Hamm’s casts this line once more and with the lids closed back on the wheelie bins, redemption through a pharmacy prescription holds out more promise than ever. But Clov is adamant it is not time. Almost as adamant as Hamm is that their relationship is improving, incanting almost conspiratorially that, ‘we’re getting on’. However, by now it was pretty obvious that Beckett was not going to let his characters escape from their Sisyphianexistence. And we are left watching as Hamm pulls out his hanker-chief and places it back over his face.

Amused and entertained by Cumming and Radcliffe’s performances, I walked back across Waterloo Bridge comfortable that if Hamm could find his misery lovelier than anyone else’s, he was welcome to it.