Friday Film : Venice film festival 2018: At Eternity’s Gate

‘Everyone thinks they know all there is about him so I didn’t feel it was necessary to tell his story in the usual biography way.’

So said director Julian Schnabel at the press conference for his new film At Eternity’s Gate. The ‘him’ is painter Vincent Van Gogh, arguably the most famous and popular artist ever. His story has intrigued everyone from Hollywood and pop stars to students who hang prints of his sunflowers on the walls of their halls of residence. The genius unrecognised in his lifetime plagued by inner demons, the self mutilation of cutting off his ear, the spells incarcerated in sanitariums, all make for a compelling, film worthy story and Van Gogh has been the subject of over a dozen films. Lust for life in 1956 starring Kirk Douglas remains the best known but there was also Vincent and Theo in the 1990s and Loving Vincent last year, the first ever fully hand painted feature film.

True to his word, though, Schnabel, himself a painter does not tread the conventional biography route. He said he developed his idea for the film after a visit to a Van Gogh exhibition. He wanted to make the film equivalent of the feeling one has after having absorbed a work of art. ‘It’s therefore impossible for me to explain the film,’ he added.

This approach translates into his taking a sensorial approach to the film with the use of jerky, handheld camerawork that captures each blade of grass, each exquisite petal as he follows the artist’s footsteps through the fields and flowers he would bring so vividly to life in his paintings. As Vincent basks in the overwhelming beauty of nature, it’s as if he is the camera through which we too can revel in it. There is a sensuality in the cinematography (by Benoit Delhomme) that draws you in and makes you feel that if you just reached out you could touch that sunflower or feel the ripple of sunlight on your fingers.

‘What do you paint,’ asks a fellow inmate at the sanitarium. ‘Sunlight’ replies Vincent. The film captures much of it just as Vincent’s paintbrush does but the screen also goes black many times like the artist’s life and over the darkness you hear Vincent’s thoughts. This too is perhaps an attempt see the world through Vincent’s eyes, to share his tortured mental state that resulted in occasional blackouts when he would have no recollection of reported violence despite his otherwise lucid take on his inner demons.

So, if the film isn’t quite a biopic, what is it?. It’s different things at different points. It is, indeed, part biopic but also part memoir from Van Gogh’s own words, part moving painting, part tragedy and even part whodunnit. It’s certainly a visual delight and painfully well acted but may have difficulty finding a large audience because it isn’t enough of any one genre.

The supporting cast, some roles almost cameos, is uniformly excellent. Oscar Isaac as Paul Gaugin, Van Gogh’s friend and contemporary who is portrayed as a more sympathetic character than Lust for Life is well cast. The two friends passionately debate life, family and the nature and purpose of art. While Gauguin wants to escape the world he knows to paint something new, Vincent wants to feverishly absorb the life around him and imbue with something from within him. ‘You over paint,’ Gauguin tells him. It’s too fast.’ But for Vincent it’s the spontaneity and speed of his paintbrush that becomes the ‘stroke of genius.’

Mads Mikkelson has a compelling cameo as a priest who comes to visit Van Gogh in the mental hospital during one of his incarcerations. They discuss Jesus and the bible, Van Gogh having once thought of a career in the church. Other passing characters too, however briefly on screen, are fleshed out by a range of experienced actors and actresses.

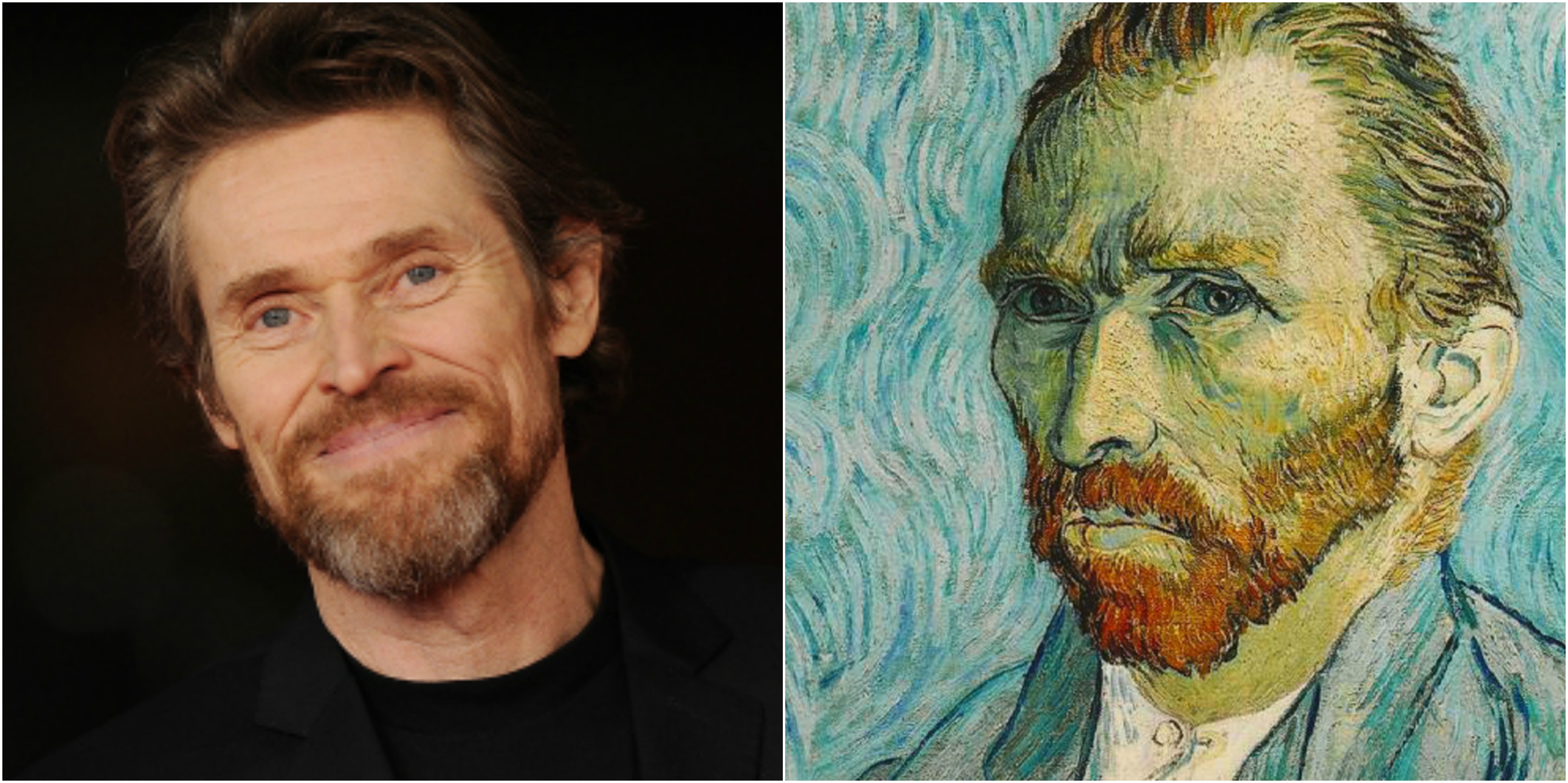

At the heart of the film, of course is Vincent himself played by Willem Dafoe who with his hollowed cheek, clear eyed, ageless face bears an uncanny resemblance to the haunted one in Van Gogh’s self portraits. His physical performance, much of it in ecstatic silence as he absorbs the beauty of nature around him before he sets to capture it on canvass, is flawless. He’s so involved in those scenes he almost makes them an interactive experience for the audience. When he speaks it’s a tiny bit jarring at first because he makes no attempt at a generic or specific European accent. This is American Van Gogh and the focus is on the words he says not how he says them. It’s a masterful performance and will almost certainly garner Dafoe awards attention. Whether that will translate into awards recognition is harder to say. Last year he was pitted against another veteran actor who had paid his dues, Sam Rockwell, in the supporting actor category and many felt he deserved the statuettes for The Florida project. That should give him a nice push. However, this film may not gain a large enough audience for him to be pushed with the wind of excitement behind him that a bigger film brings an actor.

Schnabel said Dafoe was the only actor he had in mind when he as casting the film. ‘He has the inner depth and the physical ability to play Vincent. He was the only actor I wanted and considered.’

As in Loving Vincent, At Eternity’s Gate also raises the idea of Vincent having been killed rather than taking his own life as is the accepted lore about the emotionally troubled artist.

‘I’m not conducting a forensic investigation into it,’ Schnabel shrugged at the press conference, ‘but I must say there’s no testimony of him killing himself. He returned home with a bullet in his stomach. The police never found the gun and he told them ‘don’t blame anyone else’. Why did he say that? The story that he killed himself is part of the dark, romantic legend around him but there’s evidence he wasn’t quite the sad man at the end of his life that he’s often portrayed to be.’

In his own words Van Gogh, at one point in the film says ‘ I paint with all my qualities and flaws’.

It’s a good description of this film which has a great deal to recommend it but is also at times too abstract and impressionistic to wholly love.